BEIJING — At the top of the shopping list for anyone in their late 20s or older in China is health, sports and wellness. That’s according to an Oliver Wyman survey late last year, as China finally started to end its Covid controls.

For people planning to spend more on that health category, 47% said in December they intend to spend more on health insurance. That’s up from 32% in October, the report said.

“There’s a much higher health concern after this latest wave, but after the entire pandemic the health consciousness of the Chinese consumer has increased a lot,” said Kenneth Chow, principal at Oliver Wyman.

Even for people in their early twenties, health is only second to their plans to spend more on dining, the survey found. The study ranked the categories by the percentage of respondents who said they intended to spend more on each item, minus the percentage of respondents planning to spend less.

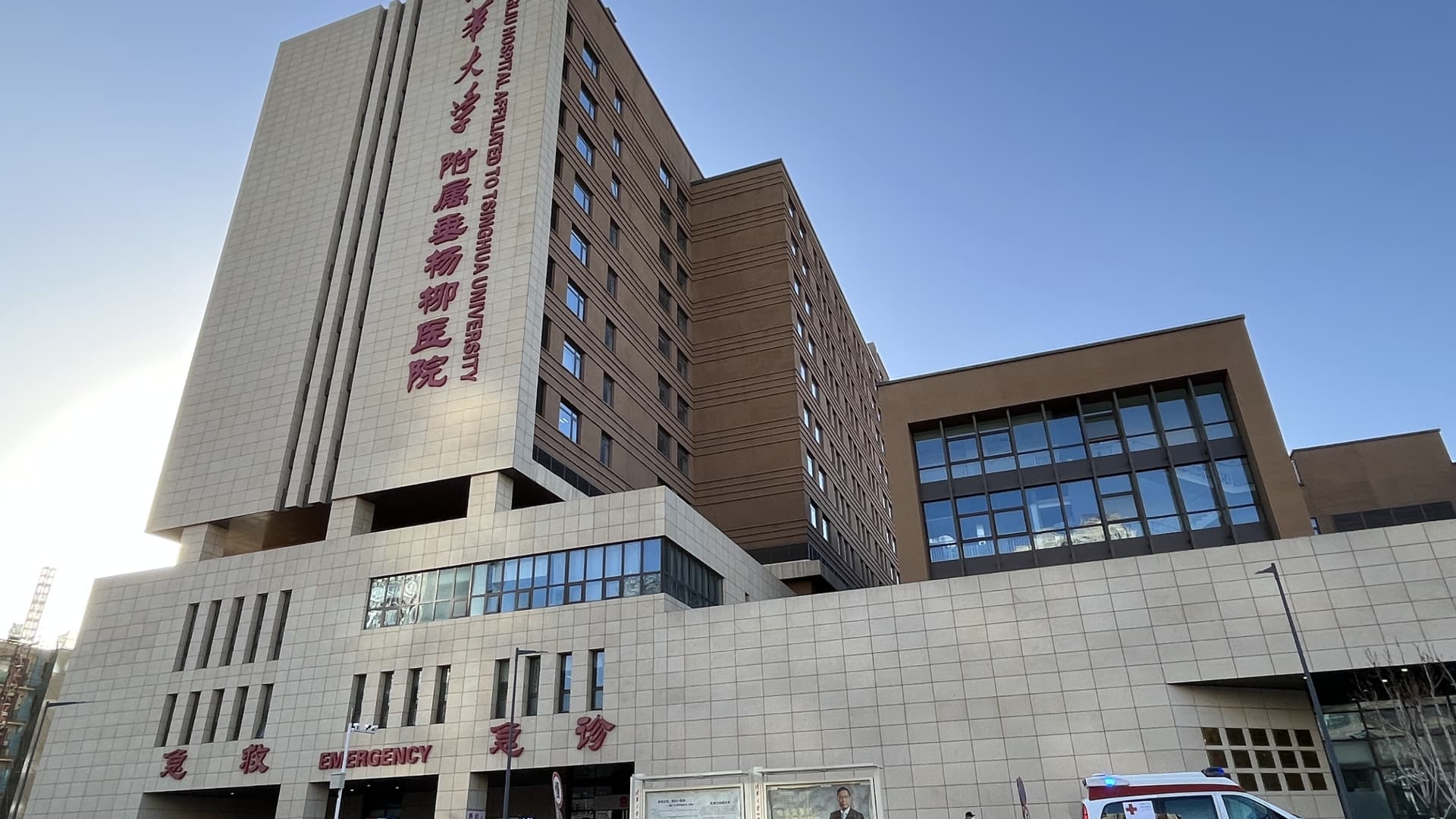

The pandemic pressured hospitals around the world. But China’s situation — especially since Covid cases surged in December — revealed the gap between the local public health system and the country’s global economic heft as second only to the U.S.

The U.S. ranks first in the world by health expenditure per person, at $10,921 in 2019, according to the World Bank. For China, the same figure was $535, similar to that of Mexico.

Households in China also pay for a higher share of their health care — 35.2% versus 11.3% for Americans, World Bank data showed.

Extreme pressure on public hospitals — including lack of capacity — drove many new patients for Covid and non-Covid care to facilities operated by United Family Healthcare in China, said founder Roberta Lipson. She said her company has 11 international-standard hospitals and more than 20 clinics in major Chinese cities.

“Growth in awareness of the importance of assured access to health care, as well as UFH as an alternative provider, is driving increased demand for our services from patients that can afford self-pay care,” she said.

“This experience is also driving increased interest in commercial health insurance which could cover access to premium private providers,” Lipson said. “We are helping patients to understand the benefits of commercial insurance. This will have a lasting impact on demand volume for private healthcare services.”

New Frontier Health, of which Lipson is vice chair, acquired United Family Healthcare from TPG in 2019.

In early December, mainland China abruptly ended its stringent Covid contact tracing measures. Infections surged, with hospitalizations reaching a high of 1.6 million nationwide on Jan. 5, official data showed.

Between Dec. 8 and Jan. 12, Chinese hospitals saw nearly 60,000 Covid-related deaths — mostly of senior citizens, according to Chinese health authorities. By Jan. 23, the total exceeded 74,000, according to CNBC estimates from official data.

Although new deaths per day have fallen sharply from the peak, the figures don’t include Covid patients who may have died at home. Anecdotes depict a public health system overwhelmed with people at the height of the wave, and long wait times for ambulances. Doctors and nurses worked overtime at hospitals, sometimes while they themselves were sick.

Health insurance

Most of the 1.4 billion people in China have what’s called social health insurance, which provides access to public hospitals and reimbursement for medicine included in a state-approved list. Employers and their staff both contribute regular payments to the government-run system.

The penetration of other health insurance — including commercial plans — was only 0.8% as of the third quarter of 2022, according to S&P Global Ratings.

Analyst WenWen Chen expects commercial health insurance to grow quickly this year and next. “Following Covid, we do see people’s risk awareness rising. For [health insurance] agents, it’s easier for them to establish conversations with clients.”

Some of the players in China’s health insurance industry include Ping An, PICC and AIA. Local authorities are also testing a low-cost insurance product called Huimin Bao.

Oliver Wyman’s survey in December found that 62% of non-policyholders planned to buy health insurance, and that 44% of existing policyholders were considering an increase in their coverage.

Over the last 15 years, the Chinese government has dedicated financial and political resources to developing the country’s public health system. The topic was an entire section in Chinese President Xi Jinping’s report at a major political meeting in October.

Hospital funding

However, one of the barriers to improving China’s public health system is its fragmented financing system, according to Qingyue Meng, executive director at Peking University’s China Center for Health Development Studies.

Health-care providers in China receive financing from four sources — social health insurance, the government health budget, essential public health programs and out-of-pocket payments — each “managed by different authorities without effective coordination in budget management and allocation,” Meng wrote in The Lancet in December.

“Hospitals and clinics are reluctant to provide public health care due to the absence of financial incentives and the important number of regulations,” he said, “which further separate[s] hospitals and [specialized public health organizations such as the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control].”

For comparison, HCA Healthcare, the largest hospital operator in the U.S., said over half of its revenue comes from managed care — often company-subsidized plans that have a network of health providers — and other insurers. Most of HCA’s other revenue comes from government-related Medicare and Medicaid health insurance plans.

In China, United Family Healthcare’s Lipson claimed that being a privately managed business allowed it to react more quickly. “We finance our own growth and can acquire talent and expertise by offering competitive pay packages, so we can also flex beds to the level of care that is needed.”

“Having observed the course that pandemic surges took in other countries, and because our patients are private pay, we were able to order sufficient supplies of medication, PPE etc, as we began to see the numbers of Covid cases grow in China,” she said.

Her company had excess capacity at the start of the pandemic since it opened four hospitals in the past two years, Lipson said, noting the public system added 80,000 intensive care unit beds over the last three years, but struggled to meet the demand from the surge in Covid cases.

A shortage of specialized doctors

Ultimately, the pandemic’s shock offers the opportunity for broader industry changes.

The health care payment system doesn’t have a direct impact on China’s hospitals, because most are directly under government oversight, said George Jiang, consulting director at Frost&Sullivan.

But he said macro events can drive needed systemic changes, such as tripling ICU capacity in a month.

China’s tiered medical system had forced doctors to compete for a few advanced intensive care departments in only the biggest cities, leading to a lack of qualified ICU physicians and hence beds, Jiang said. He said recent changes mean smaller cities now have the capacity to hire such specialized doctors — a situation China hasn’t seen in the past 15 years.

Now with more ICU beds, he expects China will need to train more doctors to that level of care.

There are many more factors behind China’s health care development, and why locals often go abroad for medical treatment.

But Jiang noted the greater use of the internet for payments and other services in China versus the U.S. means the Asian country can become the most advanced market for medical digitalization.

Chinese companies already in the space include JD Health and WeDoctor.

— CNBC’s Dan Mangan contributed to this report.

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that Roberta Lipson is founder of United Family Healthcare and vice chair of parent company New Frontier Health.